Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link

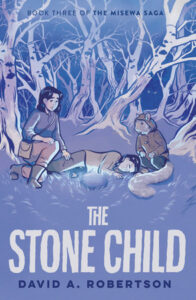

The Stone Child is book 3 in the Misewa Saga, following foster siblings Eli and Morgan, who discover that they can travel to another dimension when they put Eli’s drawings on a wall in their foster-home’s attic. Here, in Misewa, they meet animals who wear clothes and live in villages, but sometimes face major crises with which the children can help. The series incorporates Cree words and rituals, with identity as a powerful theme for the main characters, both of whom are First Nations.

This is the first book to introduce a romantic side-plot. Since it’s a middle grade novel, I hadn’t felt that was especially lacking, but it was introduced with characteristic nuance. This time Morgan’s friend Emily is along for the adventure. The girls share a nerdy friendship centered around a mutual love of outer space adventure stories, especially Star Wars; they tease each other and generally enjoy one another’s company. This would have been a perfect portrayal of a friendship even without the romance aspect.

As for the romance itself? Adorable. It progresses slowly, with little jokes and blushes, a tiny kiss on the cheek and full stop to ask if this was okay. Morgan and Emily have a relationship built on shared interests, respect for one another, open communication, and trust. Their nascent romance never rises to the center of the story, something I consider a positive. There are life-and-death stakes in this book. Morgan is struggling with her family. Though Emily is a consistent positive in her life, she’s never a distraction from Morgan’s questions of identity and belonging. One of my biggest pet peeves in any fiction is a character losing their sense of self for a romantic partner, so I adored watching Morgan stay honest to her path, even as she invited Emily to walk with her.

I don’t recommend starting with this book. The first in the series, The Barren Grounds, is the place to start. Even before Morgan and Emily’s friendship begins to wend its way toward “something more”, the series is filled with nuance—from Morgan, an angry girl with a huge and damaged heart; to her foster-mom Katie, so eager to do right but oblivious as a white woman fostering First Nations children; to how right and wrong play out on a generational scale. It’s at times heartbreaking and at other times pure delight. And, consistently, it’s an exciting adventure.