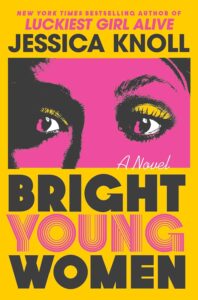

In her most ambitious novel yet, crime writer Jessica Knoll—author of Luckiest Girl Alive (2015)—blends fact and fiction as she adapts the events surrounding a series of killings committed in Tallahassee, Florida in 1978.

Bright Young Women (2023) begins in January 1978. Patricia Schumacher is president of her sorority at Florida State University. She takes pride in her organized, fair, and exacting leadership. One fateful night, Patricia is awoken in the early hours of the morning by a strange sound. What—and who—she encounters in her sorority house will change her life forever. With two of her sisters dead and two others horribly maimed, and Patricia the only woman to clearly see the man responsible, she is immediately immersed in a mystery that began long before 1978 and, unbeknownst to her, will continue for decades afterwards. Patricia’s encounter with the killer will lead her to join forces with the eccentric but driven Tina Cannon, who believes the man who entered Patricia’s sorority house that night is the same individual who abducted Ruth Wachowsky from late Sammamish State Park years before. As Patricia and Tina weave together the complex threads of this case, battling the media, misogyny, and utterly useless police along the way, a story of sisterhood and survival emerges.

Choosing to adapt the crimes of Ted Bundy for a fictional context is a bold endeavour; not only are his crimes so famous, but the misplaced mythology surrounding Bundy as a figure means that any novel dealing even in part with the murders he committed risks being overwhelmed with that mythos or worse, replicating it. Bright Young Women seems aware of these risks and actively works against centralizing Bundy: his name appears nowhere in the novel (he is only referred to as The Defendant), and Patricia and Tina repeatedly insist that whatever “power” attributed to him is actually grounded in a more widespread misogyny. Knoll puts it most succinctly when she writes that The Defendant is a “loser” and always has been. Popular culture is responsible for his overblown intellect, instinct, and criminal mind, and the man himself remains entirely below average.

Bright Young Women is more concerned with representing the women affected by these events, and the ways in which they are strengthened and drawn together by a shared goal. Patricia’s narrative voice is powerful and direct, and Tina’s devotion to Ruth is palpable throughout the entire novel. By highlighting the rampant misogyny these women face in this text, Knoll highlights that, over forty years on, we seem to be having the same conversations around victimhood, value, and blame. Bright Young Women is more than crime fiction—it reads as a stunningly critical and emotional novel about women’s lives.

While I loved the novel and I think it’s an important piece of crime fiction, I’m not sure if I can figure out what the addition of a lesbian subplot adds to the text. I can see the importance of decentering heterosexual plots in crime fiction generally, but with Bundy in the mix and with the novel ending the way it does, I’m not sure I found reading lesbians in this novel at all comforting. Perhaps being discomfort is the intention. Or perhaps the lesbian plot is self-consciously critical of the kind of victim society values (as much as it can be said to value them at all in this novel) by disrupting the narrative of the young, white, heterosexual female victim that is immediately associated with these kinds of crimes.

Regardless, while I think this novel is excellent, it is also tragic, and therefore not for everyone. I’m fascinated by Knoll’s writing in this book, and I highly recommend Bright Young Women for fans of crime fiction.

Please add Bright Young Women to your TBR on Goodreads.

Content Warnings: Murder, rape, conversion therapy, violence, death, gaslighting, homophobia.

Rachel Friars is a writer and academic living in Canada, dividing her time between Ontario and New Brunswick. When she’s not writing short fiction, she’s reading every lesbian novel she can find. Rachel holds two degrees in English literature and is currently pursuing a PhD in nineteenth-century lesbian literature and history.

You can find Rachel on Twitter @RachelMFriars or on Goodreads @Rachel Friars.