Five adults left a wedding reception in rural Wisconsin very late one night in 1983. Stoned, drunk or sleepy, none of them were in any shape for driving. Their car struck and killed a child and her death stayed with them for years. In Carry the One, Carol Anshaw explores the connections between human beings: siblings, parents, married couples, lovers and offspring, as well as fellow participants in a tragic event.

Alice, sister of the bride (Carmen), and Maude, sister of the groom (Matt), discovered a passion for each other on the night of the wedding. “All through the night Alice had tried to break down the elements of Maude, then add her up, but she kept getting lost in the higher math, the exponential blur.”

Later, arithmetic comes up again when Alice speaks of the connection between all of them who were in the car that night: “Because of the accident, we’re not just separate numbers. When you add us up, you always have to carry the one.”

“In a deep recess, an inchoate space where thoughts tumble around, smoky and unformed, Alice’s biggest fear was that she and Maude and the accident were tied in an elaborate knot — that her true punishment for what happened that night would be God, or the gods, or the cosmos giving her Maude, then taking her away.”

The strong bond between Alice and her sister, Carmen is wonderfully portrayed, as is the way they cope with Nick, their junkie of a brother.

“Their alliance was deep, formed in the trenches of childhood where they were each other’s landsmen, comrades in strategy and survival, in warding off the contempt of their parents, and in protecting their brother. These positions had been set up early and were not subject to realignment. So Alice and Carmen always approached each other carefully, with respect — minor diplomats, one from an arctic, the other from an equatorial nation, attempting to understand each other’s customs, participate in each other’s holidays.”

Twenty-five years pass over the course of the story. It’s like a trip down memory lane. For example, Nick wore a thrift shop wedding dress to Carmen’s wedding. (His sisters called him “the backup bride.”) I used to share a house in the early 80s with three other dykes and two gay men, one of whom (David) liked to wear a wedding dress that he found at a charity shop. Our friend k.d. lang later wore that very same dress to collect a Juno award for Most Promising Female Vocalist. But I digress.

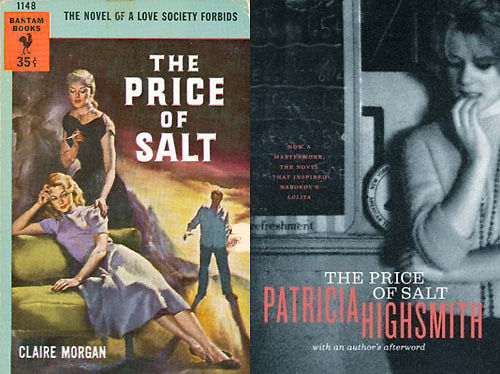

“The covers had a sinister tone, usually represented by a woman in a black or red slip. ‘They’re all great,’ she told Carmen. ‘They’re like Greek tragedies. Everyone gets horribly punished in the end. Or they hang themselves with a belt over the steam pipe.’

‘But weren’t these somebody’s real, tortured life once?’ Carmen said.

‘Well, sure, but now they’re more like folktales. Hardships of our ancestors. Like Lincoln walking ten miles to school every day through the snow. That sort of thing, only in bars.'”

Nick’s girlfriend, Olivia, was the one driving when they left the wedding. She was negligent in many things, including her job as a letter carrier. On the night of the accident, her trunk was full of undelivered mail. I was a postal worker from 1983 to 1989, so that is another reason that Anshaw hooked me from the start.

Beautiful language, great characters and a moving plot; it all adds up to a superb book.