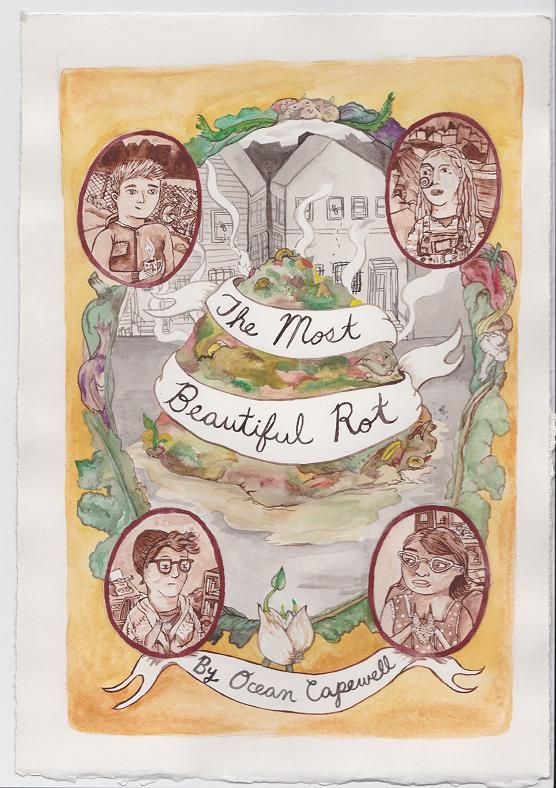

The Most Beautiful Rot is exactly what its title suggests: the story of four not-so-beautiful lives making the most out of what they are given, which, among addiction and disease, includes a literal rot – a giant compost pile in the backyard of a crumbling house in a poor urban neighborhood. Ocean Capewell is a gifted writer who weaves together four narratives into one compelling account of young, twenty-something, punkish, queerish, poorish life in the 2000s.

We first meet Tabitha, fresh out of high school and into the world of lesbian love. She follows a girlfriend across the country, is promptly dumped, and finds a home – and family – in the form of three twenty-somethings living meager lives in a run-down house with less-than-adequate amenities. Tabitha’s narrative is sweet, earnest, and full of love and possibility. From there we are tossed into Xandria’s story, which, especially on the heels of Tabitha’s personal prose, feels sterile, bland, and almost forced. At first I felt perhaps we should have stayed in Tabitha’s care, but after reading about Xandria’s resentment of Tabitha’s innocence, I realized it is a much more interesting choice if only because it made me think back on Tabitha and wonder if I did too. Next we find ourselves entangled in Jasmine’s compelling narrative, in which she is faced with a troubling diagnosis and finds herself with not much to fall back on. Jasmine’s voice is poetic and strong; it was into her world that I found myself feeling most pulled. The author succeeds in finding four distinct voices here, while delving deeper into the themes of friendship, love, hopelessness, and personal meaning with each chapter.

The last character we meet is Lydia. She is the reality check The Most Beautiful Rot needed – reminding her roommates that young white girls leaving privileged homes to live in a poor neighborhood does not mean they are “fighting oppressive forces.” (no kidding!) Lydia is truly the novel’s center of gravity. She is the most realistic of the four girls; rightfully it is through her eyes that we see their innocence lost. Her narrative concludes our time with these girls and our look into their young, messy, and sometimes tragic lives. What impressed me most about The Most Beautiful Rot was its freedom. The text moves swiftly, bubbles over, and quietly pools before babbling once again. It never lingers too long, nor does it become overly sentimental. Though there are a handful of clichés throughout, all told this book felt invigoratingly new.

The young women we come to meet have stories not often read or written. There is a sense that Capewell writes from a place she knows well, and her eagerness and honesty in sharing these girls’ lives with us makes it a refreshing read. I would recommend this book to young queer women looking for more faces like theirs in YA lit (though I wouldn’t necessarily classify this as so). Never quite fully dipping into after-school special mode, The Most Beautiful Rot does invite us to face a host of social issues, including sexual abuse, drug and alcohol addiction, disease, racism, and classism. There are characters of varying shapes, sizes, and sexual and gender identities. But sometimes the goofy political correctness shocked me out of the narrative’s momentum, and while it did beg some suspension of disbelief at points, the heart of the novel was filled with truths to which it was hard not to connect. The Most Beautiful Rot is truly a contemporary piece, and in spite of its flaws, it is a triumph for the lonely young queer kid who hopes to carve their story into marble someday.